When it comes to the human body, there are some things we cannot change: our age, genetic factors, a history of trauma. But there is a lot we can do to help manage and prevent chronic pain from limiting our lifestyle. Back pain is common. According to the CDC, nearly 60% of adults in the US report back pain within the previous 3 months (Lucas et al 2019). There’s a lot working against us. Many of us work desk jobs with poor ergonomic setups and few opportunities for position changes, leading to more load and less circulation in the spine. Others are part of the repetitive labor force, where wear and tear/overuse injuries are common from poor body mechanics and pressure management in the core. Then there’s how we spend our free time. Some of us are sedentary, others are weekend warriors, some are die-hards in their sport or training. How we accumulate injuries (or prevent them) usually boils down to some combination of our genetics, our habits, and some luck. I think that learning a bit about our anatomy and how to work with it can help drive the changes we want to see in pain levels AND our ability to do what we love.

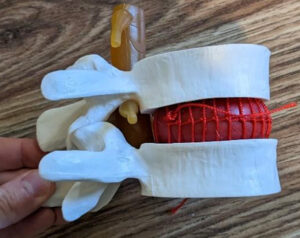

Let’s talk first about a motion segment. A motion segment is the basic unit that makes up the spine. It includes: two adjacent vertebrae (for example, L1 and L2), the disc between them, the 3 joints connecting them (two facets and the intervertebral), the nerves and spinal cord/cauda equina that pass through them, and the supporting connective tissues.

Each segment should move a little. When one starts to move more than the others, that’s when problems usually pop up. Our bodies like to cheat, and they will find the path of least resistance. If you are tight in your upper back from typing on your computer all day and your lower back is moving a lot, when you go to swing a golf club, guess where all the movement comes from and where all the stress goes? Through the hypermobile segment.

The House Analogy (Stenosis in DDD and DJD)

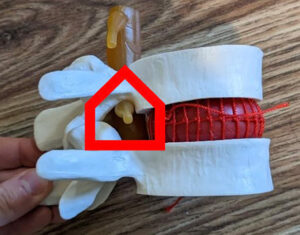

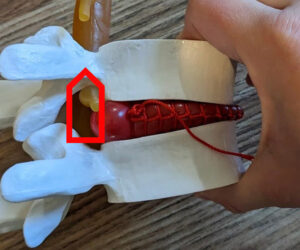

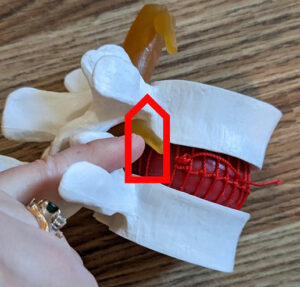

I like to think about the nerves in our spine as little people living in a house. The house is made up of the vertebrae, the discs, and the ligaments that make up the central and lateral spinal foramen. People do not want to live in a house that is too short or narrow for them to move comfortably. Nerves do not like pressure, and they do not like to stretch. If the house (the foramen) gets too small, it is called stenosis. If the nerve gets crowded and compressed, it starts to lose function. When nerves have pressure on them or cannot glide well, they tend to get irritated, resulting in complaints of changes in reflexes, strength, and sensation from radiculitis or radiculopathy.

Pressure can come from 2 things: mechanical compression and/or inflammation. Most of us have dealt with some inflammation from time to time, symptoms are transient and come and go based on activity and lifestyle. Someone with inflammation might respond well to steroids or injections for conservative medical management, and therapy is also often very helpful. Mechanical compression can have wide ranges in severity. Something (a disc, bone, or buckled ligament) is physically putting pressure on the nerve. Typically, if someone is not getting relief from oral steroids or injections, we can suspect that there is mechanical compression. Mechanical compression does not always resolve/heal, but it can improve in a lot of cases with good posture, strengthening, pressure management, and good body awareness/mechanics. Sometimes surgery is indicated and necessary due to loss of nerve function, spinal instability, or severe stenosis.

Reasons for Mechanical Compression

The disc is the primary stabilizer and shock absorber in a healthy spine. It gives height to the lateral foramen and forms part of the anterior wall of the central foramen. With degenerative disc disease (DDD), there is a gradual loss of disc height. To some extent, this is a part of aging. The nucleus pulposus, in the center of the disc, loses water content over time. With less water content, the disc loses its ability to absorb shock/manage load, and it loses height. There are 4 stages of DDD. In the first stage, the disc still has good height but is starting to lose its ability to stabilize the spine. (Clinically, we notice increased segmental motion.) As DDD progresses, the disc becomes shorter and stiffer, resulting in a loss of segmental motion and stenosis. At the end stage of DDD, we observe a natural fusion and a hard end-feel with joint play in the motion segment. Remember the house? If we are thinking about the lateral foramen, if the disc gets shorter, then the ceiling of the house is getting lower. Here is a visual where the back part of the disc is shortened on the model, and we can see the foramen is smaller. The house is shorter.

Disc herniations are another reason for back pain and mechanical compression. If we look at the annular fibers that make up the outer part of the disc, there are layers of little ligament-type structures that run at a 45 degree angle between the two vertebrae in opposing directions between layers. This gives stability in multiple directions, but also helps us to understand why certain movements are associated with herniations. We hear patients all the time say that they bent over and twisted to pick something up and felt a “pop” with instant pain. That “pop” was likely annular fiber tearing. Under flexion and rotation, some of the annular fibers are tensed and others are lax. Add too much load, especially quick rotation, and those tensed fibers that are taking all the load will fail. Superficial fiber tearing alone can be incredibly painful. If enough layers tear and there is desiccation or bulging, that’s when pressure can be placed on the nerves. Depending on the location of the herniation (more central versus more lateral) we can see lateral or central stenosis. If we think about our house again, it would be like the walls are closing in.

Herniations cannot be put back into place, but the body does have some ability to break down the disc herniations. If someone is young and healthy and their herniation is in a location with good circulation, the inflammatory response brings macrophages to the area to break down the collagen structure over weeks to months. If the herniation is under a ligament, it is less accessible to the immune system and less likely to change. The collagen breakdown results in a softer and hopefully less symptomatic herniation. If you think of the house with the wall closing in, would you rather be resting up against the soft couch or the hard end table? Probably the couch because it is less likely to compress you enough for you to complain. This is why we can see old herniations on imaging, but they can be asymptomatic or intermittently symptomatic.

In the case of herniations, forward bending can cause more pressure from the nucleus on the torn annular fibers, causing pain and increased posterior pressure. Repeated extension is not my preferred method of treatment. I find that passive extension does little to improve strength, and loads facets in a non-functional way. Active extension in muscles that are likely already painful or overworked from new hypermobility are probably not well-served by more shortening. I try to work toward restoring good stability in neutral, and then bringing motion back in when things are calmed down and stronger.

The facet joints are another common problem area. Facets allow for two types of motion: gliding and gapping. The orientation of the facets changes based on the spine region, and this determines how well we can rotate or bend. Each segment has a right and left side, and we can see hyper or hypomobility in one side or both. Facets glide with flexion/extension and sidebending, but will gap and compress with rotation. Learning about coupled and non-coupled patterns is really helpful to treat the spine at a segmental level and apply manual therapy techniques to restore normal mechanics.

What I want you to think about is this: If someone has stenosis, things that further compress the facet are going to make the house smaller. Things that decompress the facet are going to make the house bigger. You cannot move one facet without having a change in the other, so if I gap the right side, I am going to compress the left side (if one house gets bigger, the other gets smaller). If someone has right-sided lateral stenosis and the left side is healthy, you could teach a patient how to open up the right side and the left side would not be provoked. But if there is bilateral stenosis, opening one side can make the opposite side worse, so you will probably want to focus more on traction and neutral positions. I find that thinking about this often comes into play with treating scoliosis patients and younger versus older patients. In my young patient population with less pathology, I find specific and unilateral treatment at a few levels can make a huge difference and protect areas that do not need to be mobilized. In my older population with advanced stenosis, a lot of things need treatment, and longitudinal traction might give me the most bang for my treatment time.

When we start to see “arthritis” in the spine, usually people are referring to degenerative joint disease (DJD). This is often the result of disc changes causing increased demand on the facets and eventual bone spurring. Spurs here are often described as “telescoping,” meaning they extend up into the lateral foramen. If we are thinking of our house again, we can think of the walls closing in. Something to keep in mind with spurs is that sometimes they are in a location that makes traction painful. Traction is usually really helpful with stenotic patients, but sometimes the motion pulls the nerve across the spur and increases pain. Think about pulling a hose that’s attached to the side of your house. trying to reach the street. Pull too much, and you can end up pulling it into the corner it has to get around to reach the front of the house.

Ligament changes can also be a reason for mechanical compression. A common finding with stenosis is thickening or buckling of the ligamentum flavum. In our house analogy, it is another way that the walls close in. The ligamentum flavum is located on the posterior part of the central canal. When there is buckling, the ligament presses forward toward the spinal cord/cauda equina. Flexion in the spine often lengthens this ligament and reduces complaints, which is probably why patients with advancing stenosis start to spend more time in a posterior pelvic tilt or forward bending. It can be a reason why we see a positive shopping cart sign.

Management

Multifidi Training

The Multifidi run from the mammillary and transverse processes of one vertebra to the spinous process of another. These short muscles are spinal extensors, and they work eccentrically to prevent anterior translation of the vertebrae with forward bending. When discs lose some of their inherent stability, these guys work overtime to compensate and provide stability. This is usually why hypermobile spine patients complain of muscle tightness. We also tend to see atrophy in these muscles with a history of back pain. On MRI imaging, atrophy and fatty infiltration can be observed. These little muscles are an important part of the core and play a large role in stabilizing the spine, so training them needs to be a priority in management. Getting the intensity right is important. If we overtrain, we can end up feeding into pain, spasm, tightness, and compression. Here are a few exercises to work on building strength and endurance.

Hip Hinge

Learning to move from the hips and stabilize the back is an important functional movement to train. Every time someone needs to lift an object, go to the bathroom, or wash their hands, they need to have good mechanics to get there. I like to start small and use isometrics to decrease pain, and then progress to more functional movements. Mirrors or a dowel rod for feedback can be great tools. Ideally, we see the spine hold its position of comfortable curves and then get motion from the hips. Here are a few ideas to try.

Use the wall as a target for a small range of motion to get the hips back and elongate the glutes. A pillow for anterior support can be really comfortable for a patient with instability, pain, or anterolisthesis.

Start in a neutral standing position holding a dowel rod, and let it hit the back of the head between the shoulder blades and the sacrum. Create a good ZOA to start, and be sure the knees are unlocked and glutes are unclenched.

Gently brace the core and hinge forward from the hips, maintaining all three points of contact. See if you can hold for 6-10 second reps, and work to progress hold times.

Progress the ROM as you gain mastery of small ranges, and consider taking away the dowel rod and adding arm movements to challenge the core.

Work into functional patterns like a squat or deadlift, maintaining the spine’s position.

A chair can be a good way to take the lower extremities out of the movement if someone is struggling to get started. Progress to using the hip hinge with sit-to-stand training.

Superman on a Ball Levels 1-4

I like using a ball for Superman to keep the spine in a more neutral position. If performed on the floor, it creates lumbar extension, and someone dealing with stenosis is unlikely to enjoy that position. This is a great way to strengthen isometrically and then have some time in traction for unloading between repetitions. It’s also an easy position to palpate for a good contraction and make small adjustments to meet a patient’s needs. If someone is having pain, we can cue them to walk a bit lower down the ball to create a shorter lever arm.

Here is the rest position, which allows for gentle unloading of the spine with some traction. I cue for melting over the ball and gently breathing into the back.

Level 1

Arms are resting gently on the ball to make a shorter lever arm. I cue for a long spine in this position, and I think of creating a long line from the top of the head to the heels. The goal is a neutral spine with its natural lordotic curve, and not to be in extension. I start with ten second holds for ten reps, and work up to longer holds in this posture.

Level 2

The arms no longer help support. It is a big jump in difficulty to go from Level 1 to Level 2. Watch that patients don’t lose height (you should not see them flex over the ball or their chest drop down). The goal is still to hold a neutral position.

Level 3

We add movement at Level 3. The arms alternate with reaching. If you are palpating, you are looking for changes in intensity of the multifidi contraction on the right and left side as the arms move. This simulates walking with an arm swing. Small weights can be an appropriate progression if tolerated.

Level 4

I reserve this level for my younger or less stenotic population. It can be a good one for your athletes with a lot of hypermobility. The lever arm is long here as the arms are extended out. Remember, this should not cause pain. If it does, there is too much load and it is time to back off and build better strength. A small weight can also be added here for progression.

LE Extension With or Without Ball Support

Here we can train the glutes and multifidi together. The goal is to keep the spine neutral as the hip extends. The ball can be nice anterior support for a hypermobile population and it gives some good proprioceptive feedback. We can cue to make sure their ASIS does not peel away from the ball and that they are not letting the ball roll from side to side when they alternate legs. Can add the arm motion as well for more of a challenge.

Abdominals

Sarah covers this in depth often, but working on a well-balanced core is important for creating a good brace. The TA is particularly helpful in stabilizing the lumbar spine and deserves attention in this population.

Unloading

This is something I make sure to cover on Day 1 with these patients. It is important that they get good at identifying what is increasing their pain and how to address it. This gives them back a sense of control and helps to minimize flareups and severe symptoms. In advancing stenosis, DDD, or DJD, there are some permanent changes to the spine. They need to know how to manage this.

Self traction

If traction alleviates symptoms, it is a great self-care tool. Find out what positions your patient is often in, and show them ways to get in some unloading. For example, they have to sit for long meetings or they have to stand a lot.

In sitting, I cue to push down into the chair and make their bottom feel lighter. It is ok if their bottom is still on the chair, we just want less pressure coming down. Hold from 6-10 seconds and repeat for several cycles until pain decreases.

If they are able to get down on the floor or onto a bed, using a dowel or broomstick (or even their hands) right at the top of the femur can be a good way to create some unloading as well. Be sure to cue them to relax their core and back to allow for separation. We can follow the same parameters as in sitting.

Over the ball is a great position, but a bed, bar stool, desk, or counter can also be a great option. This position lets us relax and hold a little bit longer. It is also my personal favorite.

Positioning During the Day

I try to emphasize not being in one position for too long. Encourage changes in position every 20-30 minutes. Even if it means just standing up from the computer to stretch for a bit, movement helps to prevent so much cumulative load.

Walking creates natural cycles of compression and distraction. This acts like a pump to bring circulation to the area and can be very helpful. Lots of short, little walks throughout the day are key.

Lying down to get out of gravity as needed is also an important point. Gravity is not a disc’s friend. At night, when we are lying down for long periods of time, our discs have an opportunity to “rehydrate” somewhat. They are at their tallest when we first get up. As the day progresses, gravity forces out some of that moisture and we lose height. That means the house gets smaller as the day goes on, and backs can get more sensitive as the day progresses. Maybe a lunchtime lie-down is a good hack for someone on their feet all day.

Stretching for better posture to support spine curvature is another self-care topic I like to hit. Pec, hip flexor, lat, and paraspinal stretching can all help to improve posture and minimize changes to spine curvature.

In those with stiffness in the thoracic spine, I really love to teach self-PA mobilizations. Using a pool noodle, I have them start in their thoracic spine at about the level of their bra strap. I cue them to lie on the noodle and relax down until they feel a stretch. Have them hold for 20-30 seconds at each segment. If there is cracking, that is ok! But it should not be forced. Move up one inch at a time until you are at the top of the thoracic spine (not into the neck). As you get higher in the spine, a little bridge may be needed to feel a stretch. The more perpendicular the noodle is to the facet joint, the better the separation. So as the curve changes, we may need that bridge to get perpendicular again. You can add a dowel rod into the noodle to add firmness and a better intensity to the stretch. Using a pool noodle instead of a foam roller is important to get separation at the facet joint. The idea is that the pool noodle will stabilize the inferior vertebra, and gravity will allow the superior vertebra to translate posteriorly. This gaps the facets bilaterally and can help improve range of motion. When working here, be sure first that there are no contraindications to mobilizations.

Safety considerations

With all interventions, we want to make sure we are not seeing an increase in neuro symptoms. Things should always be comfortable and not increase symptoms. Progress slowly, and allow time for adaptations. Manual therapy can make a big difference in these populations! Some need a very specific level-by-level approach to evaluation and treatment, and others can do really well with general traction and management. In either case, the better we are at assessing and educating this population, the better they can be managed.

References

- Lucas JW, Connor EM, Bose J. Back, lower limb, and upper limb pain among U.S. adults, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 415. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:107894external.

You can visit Beth's website here: www.completeompt.com

or contact her by emailing this address: [email protected]