A cesarean section (or c-section) is a very common, well-established operation that many women have when delivering a child. In fact, the cesarean section surgery rate is about a third of all births in the United States of America.(1) This procedure is used for many reasons including prolonged labor, high risk pregnancy, large babies, multiples, fetal distress, breech presentation, a previous cesarean where vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) is not advised or desired, placenta previa, and cord prolapse.

When the decision to have a cesarean delivery is made before labor, it is often called a planned or scheduled cesarean.(2) This decision might also happen during labor if mother or baby is not tolerating labor well, it is thought to be taking too long, or other issues arise such as discovering the baby is in a malposition. This is typically called an unplanned cesarean. In a few cases it will be a true emergency, as is the case with a placental abruption, severe bleeding, or fetal distress.(2)

Knowing what to expect may help you feel more comfortable with the procedure as well as contribute to your healing, because knowledge is power.

Reasons for a Cesarean Birth

A cesarean section might be performed for a number of reasons, including: (3)

- Placenta previa: Part of the placenta is covering the cervix (the opening where the baby exits the uterus).

- A breech baby: The baby is not in a head-down position; instead, they are feet or bottom first.

- Fetal distress: The baby is not tolerating labor, or labor is not progressing which might necessitate an immediate delivery.

- Higher order multiples (triplets, quadruplets, etc.)

- Other maternal or fetal complications.

Talking to your practitioner before labor about why a cesarean may be necessary can give you specific information particular to your pregnancy.

You should also ask your doctor or midwife about their specific rates for cesarean section, even if you do not think you will have a cesarean birth. Be sure to ask about their low-risk cesarean rate. This is based on the number of women who fall into a category called NTSV (nulliparous term singleton vertex), or first-time mothers delivering at term with one head-down baby. The NTSV cesarean rate is more accurate in determining your risk of needing a cesarean.

Risks of C-section

A cesarean section is major abdominal surgery. In cases where there is an obvious need for the surgery as a life-saving tool, it is easier to weigh the benefits versus the risks when deciding on a c-section versus a vaginal birth. What is harder to define is when these added risks are not acceptable. This will vary from practitioner to practitioner and family to family.

There are a few major categories of risk: to the mother, to the baby, and to future pregnancies. The risks to the mother include: (4)

- Infection

- Blood clots

- Surgical injury to the urinary tract or the gastrointestinal tract

- Bleeding too much (hemorrhage)

- Needing a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus)

- A very small risk of dying

There are also risks to the baby, though some are difficult to tease out when the added risk is due to the reason a cesarean is needed, particularly in the case of fetal distress. These risks include:

- Breathing difficulties

- Being in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)

- Iatrogenic prematurity (accidental prematurity due to the timing of the surgery)

- Breastfeeding difficulties

- Being injured or cut during the surgery

Incision-related complications:

The risk of incision-related problems (such as a hernia) increases as the number of previous abdominal incisions grows. Surgical repairs might be needed.

While there are additional risks from a cesarean birth, it should also be noted that this is the most common surgical procedure in the United States, with well over 1.3 million surgeries performed every year. This means that there is constant work and improvement when possible to reduce these risks on all fronts.

Subsequent pregnancies and deliveries:

Once you have had a c-section, some practices prefer or have a policy that only allows c-sections for subsequent births, rather than a vaginal birth. However, a vaginal birth after c-section (vbac) can sometimes be an option. While it’s hard to say how many c-sections is too many for each individual, it’s generally accepted that risks increase as the number of c-sections increases. The evidence shows that the risk begins to increase even faster after the third c-section.

Subsequent c-section:

Benefits:

-Ability to plan the birth date and increased likelihood of avoiding an emergency c-section.

-Prevalence of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse is lower in women who have only given birth by c-section than for those who have given birth vaginally (the difference in rate of urinary incontinence appears to level out with increasing age).

-If fertility is no longer desired, the option for surgical sterilization.

-Lower rate of perinatal mortality and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy compared to planned vbac (0.05% vs 0.13% and 0.01% vs 0.08%).

Risks:

Women who have multiple cesarean deliveries are at increased risk of: (4)

- Problems with the placenta.

- The more c-sections you've had, the greater your risk of developing problems with the placenta, such as the placenta implanting too deeply into the uterine wall (placenta accreta) or the placenta partially or completely covering the opening of the cervix (placenta previa). Both conditions increase the risk of premature birth, excessive bleeding, the need for blood transfusion and the surgical removal of the uterus (hysterectomy).

- Complications related to adhesions.

-

- Bands of scar-like tissue (adhesions) develop during each c-section. Dense adhesions can make a c-section more difficult and increase the risk of a bladder or bowel injury and excessive bleeding.

- Incision-related complications.

- The risk of incision-related problems (such as a hernia) increases as the number of previous abdominal incisions grows. Surgical repair might be needed.

- Uterine rupture (where the scar separates during pregnancy or in labor).

- Fertility issues, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

- Decreased likelihood of breastfeeding at birth, hospital discharge at 6-8 weeks postpartum.

Every patient is different, and every case is unique. However, from the current medical evidence, most medical authorities state that if multiple c-sections are planned, the expert recommendation is to adhere to the maximum number of three.

Vaginal birth after c-section (vbac):

Women have a 72-75% chance of vaginal birth after c-section.

Benefits:

- Shorter hospital stay with faster recovery.

- Avoidance of major surgery and multiple c-sections in the future.

- Increased likelihood of future vaginal birth.

- Sense of satisfaction and empowerment in having a vaginal birth, if desired.

- Reduced risk of maternal mortality compared to planned c-section (even though it is still an extremely rare event regardless of mode of birth, 0.004% vs 0.013%).

- Increased likelihood of breastfeeding compared to c-section (increased likelihood remains even if planned vbac results in emergency c-section).

Risks:

- 25-28% chance of emergency c-section (which has an increased morbidity rate compared to a planned c-section).

- 0.5% risk of uterine rupture, with increased risk with induction and augmentation of labor.

- Potential trauma to perineum and pelvic floor.

- Increased risk of anal sphincter injury for women having a second birth following one previous c-section compared with nulliparous women (birth weight is strongest predictor, rate of instrumental birth also increases this risk).

- Increased risk of perinatal mortality (0.13% vs 0.05%).

- Increased risk of hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (0.08% vs 0.01%, with majority of cases associated with uterine rupture).

- 0.1% prospective risk of antepartum stillbirth beyond 39+0 weeks (recommended timing for planned c-section) while awaiting spontaneous labor.

Preparing for a C-section

Both the anaesthetic and bed rest associated with surgery can affect your lung function. Before your operation, it is important to optimize lung function and fitness to achieve the best results from the surgery and minimize the risk of complications. Things you can do before surgery are maintain fitness by walking daily, aiming for up to 30 minutes a day; practice deep breathing exercises, connecting with your diaphragm and pelvic floor; activate your lower TAs; and practice huffing and coughing, which will help to clear any secretions following the surgery.

Stay tuned for the next article on the C-section experience!

Recovery from a C-Section

Recovering from a cesarean section is different from healing after a vaginal birth. Not only did you birth a baby, but you also underwent major surgery. Post-c-section recovery takes time, but there are ways to ease the process. It is important to remember that even though you did not give birth vaginally, your pelvic floor was affected due to postural changes and the weight of the baby on your pelvic floor during pregnancy (more so if you had any active pushing in labor), so you will need to monitor and connect with what is happening with your pelvic floor during this recovery.

How long does a c-section take?

An average c-section takes around 45 minutes to perform.

The initial transition after surgery

C-section recovery is done in stages. Right after your surgery is over, you will be wheeled into a post-operative recovery room. Usually there are several beds in one room that are separated by curtains.

You will remain in the recovery area for a varied amount of time, depending on the type of anesthesia (general or regional) that you had. It's typically about a two to four-hour period. If you had an epidural or spinal anesthesia, you'll stay in recovery until you are able to wiggle your legs. If you've had general anesthesia, you may fall asleep and wake up repeatedly and possibly feel nauseated.

During this time, the healthcare team will monitor your vitals, check the firmness of your uterus, and assess the amount of vaginal bleeding you are having.

The best advice for recovery is to begin slowly moving as quickly as you can. You will want to start with simple things like breathing. While breathing sounds like an easy thing to do, taking a deep breath can be difficult after a c-section. You'll need to try and breathe deeply as soon as you can after surgery, and continue to do so frequently as you recover.

Some of your equipment will come with you when you move to your regular room, including your bladder catheter, blood pressure monitor, and IV. The catheter will usually be removed the day after surgery. (Make sure that you are not starting to unconsciously tighten your pelvic floor.) The IV will stay until your intestines begin working again, as evidenced by rumbling sounds and possible gas pain. Avoiding carbonated, hot or cold drinks (which can make gas worse) can help reduce your pain.

You will feel pain from the surgery, and it's important to manage it early on. The less pain you feel the more likely you are to be up and moving about, which is key to a speedy recovery. Be sure to tell your provider if you are nursing, as the pain medications can pass into breast milk. Many women stop taking their post-surgery pain medications too early or don't take them on the recommended schedule, which can lead to unnecessary pain. Your doctor may recommend around-the-clock pain management after your c-section for at least the first several days, so take your medications as prescribed and make sure you take them before the pain becomes too bad to manage.

This can help prevent the vicious cycle of "chasing the pain" where you never fully find relief. (If non-narcotic medications don't relieve your pain, talk to your doctor.) Once the first few days have passed, you can slowly alter your pain medication schedule to ease away from painkillers until you're medication-free.

Brace Yourself, and Move Carefully

Remember, you've just had a baby and major surgery! It’s important to rest and increase your activity level slowly over the course of the next six to eight weeks. Use a pillow to splint your incision when standing for the first few days, placing it directly over your incision and applying firm pressure. Supporting your incision can reduce pain and help you feel more stable. The pillow brace can also be used when coughing, laughing, sneezing, or moving from a seated to a standing position to help with discomfort. Some people also like to use a belly band or binder for support, which can help you move with less pain. Make sure you do not have it on too tightly — this way it will help to give you a little extra support without creating too much pressure on your pelvic floor. Wean off it as soon as you can move without feeling a lot of pain.

To get out of bed, bend your knees up and roll onto your side, keeping your knees together. Push up, using your forearms and hands to get to a sitting position, and as you do so, swing your legs down over the side of the bed. Sit on the edge of the bed with your feet flat on the floor, lean forward, and stand up. To get back into bed, reverse the procedure. Make sure you breathe well throughout the whole movement, and aim for good posture. Sleeping on your side with a pillow between your legs may give you more comfort and support. Avoid sleeping on your stomach for as long as this hurts.

Once you are home, you can resume daily activities — walking, light housework such as dusting and tidying, going up and down stairs, reaching and stretching. However, it’s important to monitor daily movements to help with your recovery. Because of the pain, you may prefer to lie, sit, stand or walk in a bent position. However, try to be upright as soon as possible so the scar can heal in this position. If you are bent over for too long, there may be significant restriction of the scar and shortening of the abdominal muscles. It is especially important to have good posture to keep the scar from healing in a shortened position. Good posture will put the abdominal muscles and pelvic floor in the best position for working, providing better support and reducing the strain on your back, lower abdomen and pelvic floor.

It is important to walk as soon as you can after surgery to help prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and your first walk is a big milestone in your recovery. However, hold off on rigorous walks or other exercise until you get the all-clear from your doctor at your 6-week checkup. Until then, don't lift, bend, reach high overhead, drive, or climb stairs (or limit them as much as you can, trying to do no more than two trips per day the first few weeks). A good rule of thumb is to avoid picking up anything heavier than your baby. As you transition into progressively walking and moving more, you can begin walking with help. Avoid the tendency to lean forward or look down, but instead try to stand up straight and focus on a short distance goal ahead of you. Splint your incision (your insides will feel like they are falling out, but rest assured that they are held in place by several layers of stitches and staples), and it is better to walk frequent, short bouts versus one or two longer bouts as you build up your endurance.

Make sure to ask for plenty of help, and avoid carrying anything heavier than your baby for the first 6 weeks. Also avoid such activities such as unloading washing machines, carrying loads of wet washing, scrubbing or mopping and vacuuming floors, making and stripping beds, carrying bags of shopping, picking up children, bending and squatting. When you do start lifting, caution is required for a further 6–8 weeks. Gradually increase the weight you lift until you have safely resumed your usual activities, e.g. start with light bags of shopping, half a basket of wet washing, hanging light washing on a line, etc., making sure to minimize any strain by using proper lifting techniques. Keep your posture tall, hold your baby or object close to your body, breathe, and make sure you aren’t bearing down or bracing out. If you need to hold your breath or you feel any pain as you lift, the object is too heavy. Seek help.

Also remember that even though your baby was born via your abdomen, you will still bleed vaginally and your pelvic floor is still affected during pregnancy, particularly if you did any pushing before having the c-section. You may notice an increase in the amount of bleeding if you do too much too soon, and always monitor for feelings of heaviness or a “tampon feeling.” Don’t be afraid to ask for help, and remember that even if you had time to plan ahead for cesarean recovery, aspects of your recovery might still catch you off guard.

If you have older children, choose your words carefully when talking about your recovery. Try to avoid blaming the baby for your need to rest and inability to pick them up. Instead, blame the incision. Shifting the blame can help your older child(ren) avoid bad feelings about their new sibling.

Good Bladder and Bowel Habits

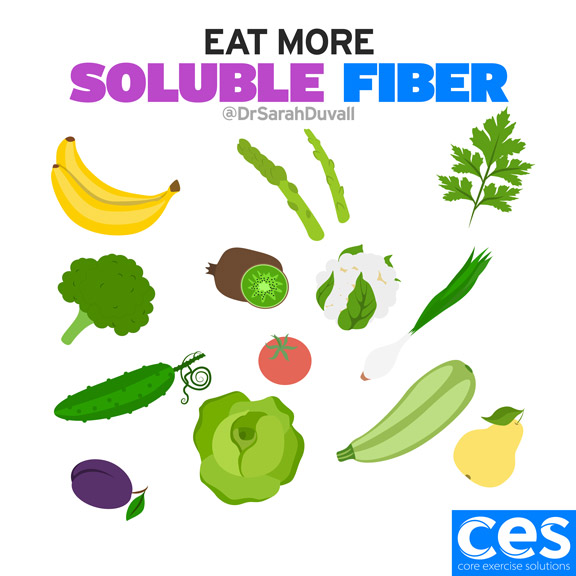

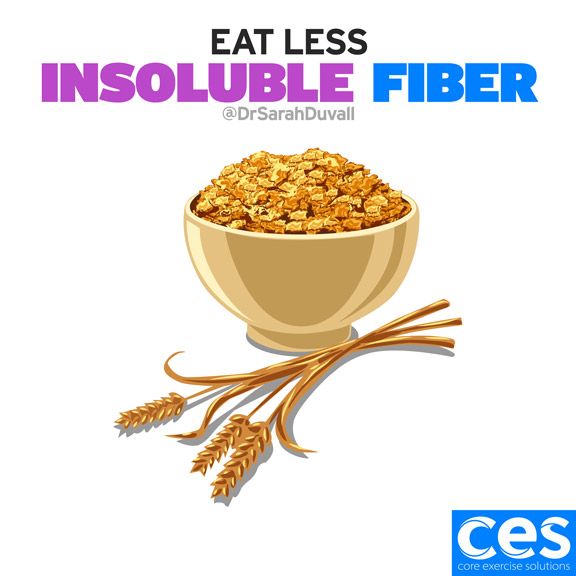

Postpartum constipation is common, but it can be made even worse by a c-section delivery and narcotic pain medication, both of which can slow digestion. Stool softeners are commonly offered in the hospital post-birth and are recommended in the early postpartum recovery period at home. The last thing you want to be doing at this point is bearing down to try and have a bowel movement! This will add pressure to your pelvic floor, c-section stitches, and linea alba that are all healing from your pregnancy and birth. Chronic constipation can increase the risk of prolapse, even if you had a c-section. You need to make sure you do not strain to open your bowels, as this may put pressure on your stitches as well as keep your pelvic floor from feeling happy postpartum.

Also note that water retention will get worse after the c-section before it gets better, meaning you might have increased swelling in your ankles and feet. It’s important to stay hydrated, get up and move, and take your meds as prescribed by your doctor, as all of this helps with water retention as well as your healing.

C-section incision

Don't be afraid to look at your incision. It's actually very important that you do, as you will need to monitor it for signs of an infection. (This is also a good time to connect with your belly, and take a moment to appreciate it from the bottom of your heart.) The incision might be covered by gauze on the first day, and you might also have special drains to help remove fluids that are collecting on the inside. There are different types of external incisions that may not match the incision on your uterus. Make sure to ask the provider who performed the surgery about your uterine incision.

The area may look bruised, red, and irritated. You will notice that there are staples or stitches. These will usually be removed within a few days of the surgery or they will dissolve on their own, like the internal stitches. Looking at the incision now will help you note and report changes that could indicate infection to your provider.

One thing that surprises many people after surgery is the numbness and itching. Numbness after c-section is completely normal. It will usually go away in a few weeks but doesn't always, and it does not mean that there is something wrong. Itching is a sign your body is healing — but excessive itchiness or itching that gets worse instead of better could be a sign of infection. If itching is excessive or if you have a fever, difficulty breathing, severe pain, abnormal drainage, or bleeding, contact your doctor right away. Try your best not to scratch your incision. Ice packs applied to the incision can help reduce unpleasant sensations on and around the incision site, including itching, pain, and swelling. Research has found that ice packs reduce postoperative pain and narcotic use when used after major abdominal surgery. Dermatologists recommend using petroleum jelly on the incision to keep it moist and help prevent itching.

As long as the wound is not weeping or moist at all and you are cleared by your doctor, you may begin gently massaging along and across the scar at about 6 weeks post-op with a topical moisturizer, and progressively work the scar more intensely to make sure that all the layers move well. This will help the c-section scar tissue become flatter and smoother and also prevent dryness, as well as improve the ability for you to engage your lower abs. This may take some consistent work every day or every other day, depending on how your body reacts. The goal is to lift your scar and have it feel almost the same as the tissue surrounding the scar. You might also want to add abdominal massage to your nightly routine after you are cleared by your doctor. This helps to release the different layers of your scar tissue in more depth. Having an appointment with a pelvic floor physical therapist can help educate you on proper scar and abdominal massage for optimal healing, and would also be advised if you are having problems with painful scar tissue.

Sunscreens (SPF 30 or higher) may help prevent dark discoloration of the scar. It can take 1–2 years for the discoloration to fade. To promote general healing of the scar, Vitamin E, aloe vera and silicone gels are shown to be helpful. Also, after the wound has healed, a tape applied over the scar can work wonders!

When Can I Exercise After C-Section?

Rest is important, but so too is appropriate exercise, and the two should be balanced. Thirty minutes of moderate exercise daily will improve your recovery, help achieve and maintain a healthy weight, facilitate mental well-being, improve sleep patterns, and help keep your bowels moving, all of which can make you feel happy and healthy. It is important to let your incision and body heal from the surgery and to ease into increases in your activity level, even as you get the “all clear” from your doctor at the typical 6-week checkup to resume activity. Listen to your body! If an activity gives you pain or a pulling sensation, STOP and rest. Wait a few days before trying that activity again.

Breathing exercises

Breathing exercises help reduce the effects of the anaesthetic and prevent complications with the lungs, such as collapse and pneumonia. Good, deep breathing will help with your recovery. Sit up in bed with your knees bent and feet flat. Relax your shoulders and support the incision with both hands to increase your feeling of comfort. Breathe out gently, then take a slow deep breath, getting in as much air as possible, sending the air into your sides, back and pelvic floor. Relax, and breathe out gently. Take your time. Try to do 10 deep breaths each waking hour. Try also to do the deep breathing exercises sitting in a chair, standing and walking. You may even ask for a respiratory therapist to come to your hospital room to work with you on this. Some of the harder breathing with forceful exhales will hurt for a while, and may be strenuous on your abs for about 4-6 weeks. You’ll want to continue working on breathing and posture as you heal, knowing that both will affect how your abs and pelvic floor function and assist in your recovery.

Pelvic floor and core exercises

Getting your pelvic floor muscles and TAs in a healthy balance is very important to help with your c-section recovery. You may start these around 4 weeks post-surgery or wait until the 6 week post-op clinic visit before starting them to ensure everything is well-healed and you are doing the exercises correctly.

At the clinic visit you will see one of the surgeons, but you can also ask for a referral to see the physiotherapist who will be able to assess your pelvic floor and core function. Remember that it’s not just about what you do but also how you do it, making sure your engagement is balanced in your abs and pelvic floor as well as being able to obtain full relaxation in your pelvic floor.

General fitness

Walking is an easy and safe way to start your recovery and stay fit, however any exercise program must be started slowly and gradually increased. You can even start this journey the day after your surgery (unless restricted by medical or nursing staff) by walking in your room and around the ward several times a day, increasing the duration as you feel stronger with less pain. When you leave the hospital, gradually increase the time you walk from 30 minutes daily in the first week, up to 60 minutes daily (unless restricted for other reasons) by 6 weeks. Initially you should break the walk into small bursts, e.g. 6x5 minutes or 3x10 minutes. Avoid walking up or down steep slopes and over uneven or unstable ground in the first 3-4 weeks, as this may cause more strain on your incision site.

After 10-12 weeks, if your incision is healing well, you have had no complications, and are cleared by the doctor, you may begin to transition into exercising more physically. Slowly increase the demand and make sure to monitor form and technique and how your abs engage during all activities to optimize your recovery. More on this can be found here:

Stay tuned for a future article on exercising after a c-section!

Activities to be avoided

Sports such as netball, squash, running, and high impact aerobics can put a lot of strain on healing tissues and may need to be avoided for up to 6 months. Swimming can typically be started 6-8 weeks after your incision has fully healed, your lochia (vaginal bleeding after birth) has finished, and you are cleared by your doctor, again gently progressing into it. If you have a specific sporting interest, discuss this with your physiotherapist. Everyone's body has a different timeline for what it can handle on this recovery journey, so it’s important to ease into activities and see how your body responds before advancing further. Be especially careful with activities that cause a sudden and/or high increase in intra-abdominal pressure, such as walking a dog, because they can put strain on your abdomen as well as your pelvic floor.

Overall, it is important to remember that a c-section is a major abdominal surgery and it will take some time for your body to heal and recover from it and your pregnancy. Make sure to get adequate rest and assistance in the beginning of the recovery, stay ahead of the pain, and slowly and progressively increase your activity as tolerated.

This article was written by Anna Hammond and Annatina Schorno-Pitsch, they are both amazing Physical Therapist that work at Core Exercise Solutions. You can find out more information about them here.

References:

- Hamilton BE, Hoyert DL, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2010–2011. Pediatrics. 2013 Mar 1;131(3):548-58. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3769

- Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise J-M, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):693-711. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026

https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(14)00055-6/fulltext - American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Cesarean birth. Updated May 2018

https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/cesarean-birth?utm_source=redirect&utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=int - American Society of Anesthesiologists. Procedures: C-Section. https://www.asahq.org/madeforthismoment/preparing-for-surgery/procedures/c-section/

- Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(1):e1002494. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002494

https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002494 - https://www.verywellfamily.com/giving-birth-by-c-section-2758508#cesarean-scar

Pelvic Floor and Diastasis: What You Need to Know About Pressure Management

Join us today for this 6-part Pelvic Floor and Diastasis Video Series, absolutely free.

This course is designed for health/wellness professionals, but we encourage anyone interested in learning more about the pelvic floor and diastasis to sign up.

We don't spam or give your information to any third parties. View our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.